FIRE STARTER

Theo thinks he’s Christ. At my first attempt to eat breakfast in the retreat’s communal dining room, he’s shouting:

‘I can save some of you but I won’t be able to save all of you!’

‘That’s fine, Theo, do whatever you can,’ Simon the warden replies, pulling him away

Later, as I try to eat, I hear sobbing coming from the lounge.

Simon’s head appears around the doorway: ‘Theo has had an unfortunate accident, kids,’ he says, ‘and won’t be staying with us for a while.’

Simon’s wife, Ursula, wears tight purple leggings that smell of citrus and sandalwood. She looks young for fifty, and speaks as if she’s a WW2 German spy expertly repeating dated bookish English, a Teutonic phrase occasionally intervening between exacting vowels and corrective grammar. She is also a healer.

I lie on my bed, eyes closed, head propped on a mound of pillows as she kneels beside me, lightly stroking my left temple, my face turned into the soapy incense of her legs, soothing purples filling my eyelids.

‘Breathe in the calm beautiful energy of God’s nature. God loves you if you are good, and he loves you even more if you are bad. God loves you and so does everyone else.’

‘Even Theo?’

‘Especially, this Theo,’ she replies.

At lunch, a woman called Ruth helps out in the dining room; a silent waitress in her early thirties with piercing eyes peeping out from under a thick dark fringe. I’m struggling with finishing my salad and she notices, sighing slightly as she takes the plate away, her hip brushing the corner of the table, making my glass tremble.

I notice the fine bead of a gold chain around her neck, the unmistakeable outstretched outline of a crucifix nestling under her blouse.

‘Used to be a nun, we’re lucky to have her,’ Simon tells me later in the lounge. ‘Doesn’t say much; goes with the territory I suppose.’

‘Maybe it was a silent order.’

‘No, I don’t think so, unless you know more than I do. Now, Ursula tells me you saw purple in the healing session. That’s a good sign, purple is the colour of celestial healing, just don’t think too much about her body, that’s my domain.’ He notices my cuts and scars. ‘Tickle them away?’

‘No, Christ, no,’ I say, and get out of the room.

‘Tickling is God’s way of making uptight shits loosen up,’ he shouts after me.

My heart is racing as I climb the stairs to my room. When I look back, Ruth is standing at the bottom of the staircase. She’s smiling, and it’s such a beautiful smile.

A note arrives under my bedroom door that night: ‘Simon wants me dead. You need to help me.’ No signature, no clue to who’d written it, except it’d been scrawled in green ballpoint on an A4 page torn from a notebook, its left side frayed and jagged. Find the green pen, and find the notebook and join the tear left by the torn-out page like Poirot might do? Instead, I rip the page up and drop the pieces in my bin like a guilty person might do.

Later, I dream of Theo standing in the middle of the lawn under an enormous yellow moon but as I call out to him, he slides the reconstructed note into his mouth like he’s feeding a shredder, regurgitating it seconds later like ticker tape onto the grass, and, when I wake up to check my bin, all the pieces of the note have gone.

At breakfast Ursula suggests I’m spending too much time on my own, and invites me to a group hug session taking place in the lounge at eleven.

I find a quiet corner of the garden so I can collect my thoughts before the session. But Theo is waiting, a bloody bandage wrapped loosely over his head. He sucks on a cigarette, a glint of red in his eyes when he notices the scars on my arms.

Before I can get away, he starts: ‘I knew you’d come. I was here in the garden last night but you weren’t ready to listen to my thoughts. So, I climbed on top of a hill but the masses weren’t receptive either. I stretched out my arms to give them a sign, drew the clouds apart as if I was pulling open a pair of curtains – ‘

‘Theo, you’re tired, why don’t you – ‘

‘Shut your mouth! I divided the sky in two, one half, the light side, for the good and the righteous, the second, the dark side, for the bad and the sinners. I didn’t know what side to put you in but I know where to put him!’

Out of the corner of my eye I see Simon arriving with a big heavy-looking branch in his hand.

‘Fuck off, Theo!’ he shouts.

Theo calmly stubs the cigarette out in the palm of his hand, and turns to me. ‘You can save yourself, it’s up to you, but a great darkness is coming, I promise you that.’

As Theo walks away, Simon leans into me, his breath reeking of alcohol. ‘Don’t feed the nutcase; starve him or batter him, or he’ll batter you. Here, you might need this,’ and he hands me the branch.

I take it from him

He laughs. ‘Oh, please, just drop it, I was joking.’

I walk back towards the house. When I look up, Ruth is standing at my bedroom window. She gives a shy wave to suggest she’s seen it all, and is on my side, and is there to help.

The hug session starts with a pep talk by Ursula, suggesting that if someone becomes aroused to just ignore it, as it’s ‘perfectly normal for youth to react in this way when touched’. She also mentions the solar eclipse that is going to happen tomorrow. ‘Apocalyptic times’ she says, ‘we must dig deep and harness positivity, white Christian magic, not black, and reach through darkness towards the light of the stars and beyond. Yes?’

‘Yes,’ we murmur.

There are four of us at the session − how did the others get out of it? –Ryan, Saskia, Helen and me. Saskia is slumped in a wheelchair and I’m relieved when I’m not coupled with her. That leaves Helen, who is as embarrassed and shut-off as I am. We approach each other hesitantly, my palms leaking dread, and our eyes meet for a split second before we look quickly away and nervously laugh. When I put my arms around her I can feel sweat through her shirt along her back. She whispers, ‘I hate this so much’ in my ear.

‘Good,’ says Ursula, ’see us humans are meant to touch; it’s how we came into the world, after all. And it’s not so bad, is it?’ Saskia’s motorised wheelchair makes a nervous sound and Helen and I blush.

‘Now, you need to take off the socks because we are going to get to know each other’s lovely feet. Feet are important, their soles our imprint on the earth, their name no accident for all bodies, all souls are welcome in the kingdom of God, in nature and in this world: one and the same, all of us, Amen.’

‘Amen,’ we say and begin to slip off our socks, a pungent febrile desperation filling the room; Ryan on his knees as if in prayer, tugging away at the clasps on Saskia’s heavy orthopedic boots.

After a few minutes, with Helen’s feet imbedded in my lap, slippery and glistening with sandalwood oil, Ruth arrives with a tray of tea and biscuits. Our savior! She smiles, a wry kink at the right-hand corner of her top lip, her eyes as calm as a still summer lake, sparkling, reflecting warmth, welcoming us into the deep.

I write about Ruth on my bed that night, her beatific smile, her solid naturalness and quiet unusual beauty, the otherworldly way she sometimes looks straight at me, holding her gaze a little too long. A subconscious love heart doodle frames her name as I write, the ‘R’ and ‘h’ in Ruth metamorphosing into two figures, he and her, lying head to tail, the valley of the ‘u’ like a cupped breast, the ‘t’, I have no idea about the ‘t’, but my mind is melting.

Then, I hear the sound of breaking glass and shouts from outside: ‘I want my bed back, so, for Christ’s sake, get down here and let me in!’

‘Go away, Simon, sober up and come back in the morning!’

‘I’ll smash another window, so help me. Now let me in or I’ll torch the house and everyone in it.’

‘Simon, I’m ringing the police’

‘You do that, Ursula, and I’ll torch them too!’

I look out of the window, and can just make out Simon running away from the house, across the lawn, and disappearing into the trees.

The morning of the eclipse and the house is in a heightened expectant state. In the lounge, Ursula is alternately chanting and praying with Saskia. Before lunch we’re given our protective glasses and join together in a circle in the garden to hear Ursula speak:

‘God, bringer of light, bringer of life and health for all, please will you allow us a moment of darkness to appreciate your energy once again, and then allow us to step into the warm rays of your forgiveness and light. Amen.’

‘Amen,’ we reply.

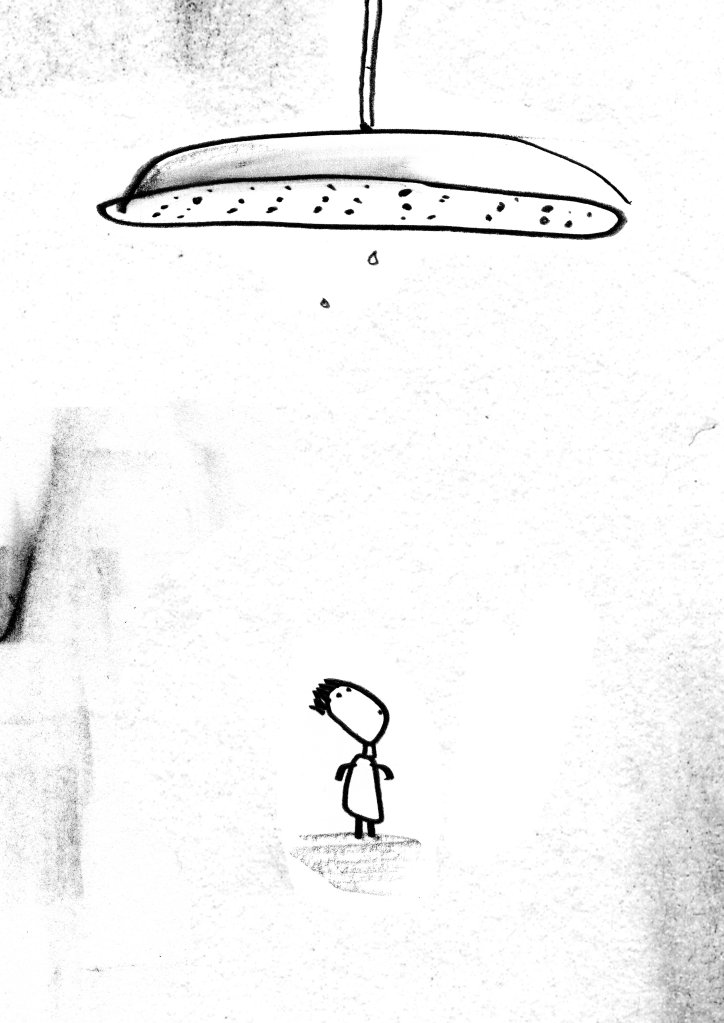

I go back to my room to ready myself for the eclipse beginning, but the sky is already darkening, the elements tightly sprung, a shrill warning call from birds in the trees, dogs wildly barking, sheep in the fields bleating like banshees.

I rush down to the garden. I’ve forgotten my protective glasses but I realise they won’t be needed. It’s very cloudy; there will be no dramatic change to the sun to view, no glowing emerging rim of light to hide from. It’s become spectacularly dark, airless, atoms all confused; animals that had been unsettled and vocal suddenly silenced.

I trip over something large and stumble forward, falling onto the ground. Ursula is on all fours, slapping, ‘smack’, ‘smack’, ‘smack’, the face of a man lying on his back on the lawn.‘I need to wake him or he’ll start fitting again. Here, help me roll him onto his side.’

I crawl over and pull his body towards me.

‘Thank you,’ she says, and reaches into his mouth to pull back his tongue, Simon’s legs twitching, a moan from deep inside his chest confirming that he’s still alive.

Tall red spikes of light jag above a bush behind them, and Theo arrives on the lawn swinging a flaming stick above his head. He runs past Saskia who dances unsteadily around an upturned wheelchair. Sparks scatter, the crackling sound of scorched wood; the pungent smell of sulphur as he gets near to us. Ruth walks purposefully from the house to stand in his way, licks from the stick’s flame reflected in her eyes. She holds out her arms to welcome him. Theo stops and prods the stick toward her, flickers of fire falling to the ground and dying by her feet. She stays still, her arms held open, and smiles. Theo drops the stick and walks slowly into her embrace. She holds him, and then frees one arm to invite me in too.

I feel myself give in as she rocks us, strands of her hair across my lips and in my mouth, salty and thick, the scent of fresh amber soap on her skin. She kisses me, her lips warm and soft, and kisses Theo, then turns us around so we are facing each other, she magically in-between. I can see crude green ink love hearts on Theo’s cheeks. We hug, but as light returns, she’s gone.

Theo and I hold on to each other, the scars on my arms disappeared, the grass catching fire behind us.

*

Fire Starter came second in this year’s RTÉ Short Story Competition in honour of Francis MacManus. Hear actor Rory Nolan do a brilliant reading of the story here: https://www.rte.ie/radio/radio1/clips/22157062/